Por León Valencia

OPINIÓN

Al reconocer la financiación de los paramilitares, la Chiquita Brands tuvo que pagar al fisco norteamericano 25 millones de dólares, pero no ha girado un peso para el Estado colombiano.

Sábado 28 Mayo 2011

Las autoridades colombianas tienen un gran desafío: encontrar el camino jurídico para que la empresa multinacional Chiquita Brands responda por la reparación de las víctimas de Urabá y para que sus directivos lleguen a los tribunales nacionales a un juicio por concierto para delinquir agravado. Es algo más que una cuestión de honor. Es una lección histórica para quienes han abusado de nuestra nación y han pisoteado nuestro territorio.

Esta empresa ha cometido un crimen sin nombre contra Colombia. Es una infamia mayor que la sociedad colombiana no puede pasar por alto. Ya los voceros de la casa matriz reconocieron, ante un tribunal en Estados Unidos, que entregaron dinero a los hermanos Castaño para financiar la guerra paramilitar en la región donde se gestó el modelo de control territorial y político que las Autodefensas exportaron a todo el país. Algo más aberrante. En un informe de la Secretaría General de la OEA se puede leer que esta empresa participó en la operación mediante la cual los paramilitares ingresaron tres mil fusiles con los cuales se cometieron parte de los 175.000 asesinatos que los mandos paras han confesado ante la Unidad de Justicia y Paz de la Fiscalía.

Por su parte Raúl Hasbún, empresario bananero, en su proceso judicial, ha declarado que Charles Caiser, gerente de Banadex, filial de Chiquita Brands junto a Reynaldo Escobar e Irwin Bernal, también directivos de la empresa, se reunió en 1997 con Carlos Castaño para pactar que entregarían, a través de las cooperativas de seguridad Convivir, a los paramilitares, tres centavos de dólar por cada caja de banano exportada.

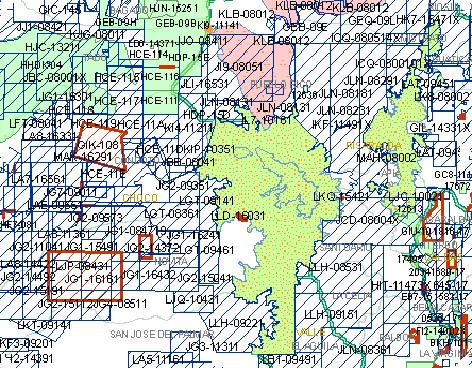

Hasbún cuenta que su idea era montar una Convivir, pero la meta de la Gobernación de Antioquia, encabezada por Álvaro Uribe Vélez, era conformar muchas más, entonces pusieron a funcionar doce. Actuaban en los cuatro municipios que conforman el eje bananero, pero la coordinación central estaba en manos de la Convivir Papagayo, a la que llegaban todos los dineros que aportaban las empresas bananeras.

La magnitud de esta operación, en la que participaron todas las grandes empresas bananeras lideradas por Chiquita, es monumental. Entre 1997 y 2004 salieron de Colombia 647.706.429 cajas de banano y llegaron a las arcas paramilitares 19. 431.193 dólares.

Estas evidencias que involucran a la multinacional en tráfico de armas, concertación con ilegales y financiación de los paramilitares llevaron a que el fiscal Mario Iguarán dijera, en algún momento, que pediría la extradición de ocho directivos de la empresa para que respondieran en Colombia por los hechos.

Las armas y la financiación aportadas por los bananeros contribuyeron a una catástrofe humanitaria en Urabá. Entre 1997 y 2003 se produjeron cerca de 3.000 homicidios, hubo alrededor de 60.000 desplazados y se cometieron 62 masacres. Pero también le dieron un gran impulso a la expansión de los paramilitares por todo el país.

Al reconocer la financiación de los paramilitares, la Chiquita Brands tuvo que pagar al fisco de Estados Unidos la suma de 25 millones de dólares y no ha girado un solo peso para el Estado colombiano. Una verdadera ironía porque el daño se hizo en Colombia y el lucro que permitió esta gran operación criminal se obtuvo también en estas tierras.

Y hagamos cuentas. Si Chiquita Brands tuviese que entregar a Colombia apenas una suma equivalente a la que hubo de pagar en Estados Unidos, se podría indemnizar con 40 salarios mínimos a más de la mitad de los afectados en el derecho a la vida en Urabá en la época nefasta en que la empresa operó en la región.

Pero la sanción a la Chiquita Brands en Colombia y la extradición de los extranjeros que participaron en estos graves delitos tendrían una repercusión mayor: el Estado colombiano abriría las puertas para investigar a todas las empresas foráneas que incentivaron el crimen y el terror en el país y, a la vez, enviaría un mensaje muy contundente a las multinacionales que llegan ahora para aprovechar el boom minero que se está gestando.

Por su parte Raúl Hasbún, empresario bananero, en su proceso judicial, ha declarado que Charles Caiser, gerente de Banadex, filial de Chiquita Brands junto a Reynaldo Escobar e Irwin Bernal, también directivos de la empresa, se reunió en 1997 con Carlos Castaño para pactar que entregarían, a través de las cooperativas de seguridad Convivir, a los paramilitares, tres centavos de dólar por cada caja de banano exportada.

Hasbún cuenta que su idea era montar una Convivir, pero la meta de la Gobernación de Antioquia, encabezada por Álvaro Uribe Vélez, era conformar muchas más, entonces pusieron a funcionar doce. Actuaban en los cuatro municipios que conforman el eje bananero, pero la coordinación central estaba en manos de la Convivir Papagayo, a la que llegaban todos los dineros que aportaban las empresas bananeras.

La magnitud de esta operación, en la que participaron todas las grandes empresas bananeras lideradas por Chiquita, es monumental. Entre 1997 y 2004 salieron de Colombia 647.706.429 cajas de banano y llegaron a las arcas paramilitares 19. 431.193 dólares.

Estas evidencias que involucran a la multinacional en tráfico de armas, concertación con ilegales y financiación de los paramilitares llevaron a que el fiscal Mario Iguarán dijera, en algún momento, que pediría la extradición de ocho directivos de la empresa para que respondieran en Colombia por los hechos.

Las armas y la financiación aportadas por los bananeros contribuyeron a una catástrofe humanitaria en Urabá. Entre 1997 y 2003 se produjeron cerca de 3.000 homicidios, hubo alrededor de 60.000 desplazados y se cometieron 62 masacres. Pero también le dieron un gran impulso a la expansión de los paramilitares por todo el país.

Al reconocer la financiación de los paramilitares, la Chiquita Brands tuvo que pagar al fisco de Estados Unidos la suma de 25 millones de dólares y no ha girado un solo peso para el Estado colombiano. Una verdadera ironía porque el daño se hizo en Colombia y el lucro que permitió esta gran operación criminal se obtuvo también en estas tierras.

Y hagamos cuentas. Si Chiquita Brands tuviese que entregar a Colombia apenas una suma equivalente a la que hubo de pagar en Estados Unidos, se podría indemnizar con 40 salarios mínimos a más de la mitad de los afectados en el derecho a la vida en Urabá en la época nefasta en que la empresa operó en la región.

Pero la sanción a la Chiquita Brands en Colombia y la extradición de los extranjeros que participaron en estos graves delitos tendrían una repercusión mayor: el Estado colombiano abriría las puertas para investigar a todas las empresas foráneas que incentivaron el crimen y el terror en el país y, a la vez, enviaría un mensaje muy contundente a las multinacionales que llegan ahora para aprovechar el boom minero que se está gestando.